Static, Stack, and Heap-Dynamic Allocation of Memory Locations for Variables and Data in TinyJ, Java, C++, and Lisp

Static Allocation

What are statically allocated memory locations used for?

In C++, global variables are given statically allocated memory locations, as are static local variables of functions and static variables of classes. In addition, characters of C++ string literals are stored in statically allocated memory locations. (These statements do not apply to variables and string literals of libraries that are loaded by a program while it is executing.)

In TinyJ, static variables—which are analogous to global variables of C++—are given statically allocated locations, and TinyJ string literals are also stored in statically allocated locations.

When are statically allocated memory locations allocated?

They are allocated before program execution begins.

When are statically allocated memory locations deallocated?

Never: The locations remain allocated for their original purposes until the program terminates.

Note on Java and Lisp

Java and Lisp are languages that do not use static allocation as defined above: In these languages, memory for all variables and stored data is allocated during program execution.

Memory for static variables of a Java class is allocated (in a part of what the JVM specification calls the “Method Area”) when that class is loaded. A typical JVM won’t load a class until it or one of its subclasses is “used” for the first time during code execution. A class is “used” when one of the following occurs: an instance of the class is created, or a static method of the class is called, or a static variable of the class is accessed. The JVM maintains a pool of cached String objects in a part of its heap. During code execution, string literals that have the same character sequence always refer to the same String object in the pool; that String object is created in the pool the first time the JVM loads a class in which a string literal with that character sequence occurs (except in unusual cases where a String object with the same character sequence is already in the pool at that time).

Stack Memory Allocation

Stack memory allocation allocates locations from an area of memory that is called a stack. Locations are deallocated from a stack in “last-in first-out” (more precisely, “last-allocated first-deallocated”) order.

What kinds of variable and data are stack-allocated memory locations used for in Java, C++, and TinyJ?

(a) Conceptually, formal parameters and other local variables of a function / method are given stack-allocated memory locations.

(b) When evaluating an expression, the values of its operand subexpressions are, conceptually, placed in stack-allocated locations, as is the value of the expression itself.

Here “conceptually” means that the program behaves in most respects as if the items mentioned in (a) and (b) are all given stack-allocated memory locations. Some compilers (including the TinyJ compiler and Java bytecode compilers) do actually give stack-allocated locations to those items. But other compilers may not give such locations to all of those items. A compiler may well take advantage of its target processor’s instruction set to generate more efficient code that achieves the same effect on that processor––e.g., it may put some values in processor registers, and (regarding (b)) it may not allocate any stack location to store the value of an operand subexpression that is a variable (which will already have a location) or is a constant that can be an immediate operand of an instruction.

Note on TinyJ VM Stacks

The TinyJ VM uses two different stacks for (a) and (b). The stack used for (a) is part of the TinyJ VM’s memory; a separate stack called the EXPRSTACK is used for (b).

When are these stack-allocated memory locations allocated?

They are allocated for purpose (a) above when a function / method is called during program execution. They are allocated for purpose (b) either when the function / method that contains the expression is called or (as happens in the TinyJ VM) while the expression is being evaluated.

When are these stack-allocated memory locations deallocated?

The locations that are allocated when a function / method is called will be deallocated when the called function / method returns control to its caller. A location that is allocated while an expression is being evaluated to store the value of a subexpression or the expression itself will be deallocated after the value has been used.

Heap-Dynamic Allocation

Heap-dynamic allocation allocates memory locations in a part of memory that is called the heap.

What are heap-dynamically allocated memory locations used for?

In Java, all Objects (including arrays) are stored in the heap. In TinyJ, arrays are stored in the heap. In C++, data items created using new, std::make_unique, or std::make_shared are stored in the heap. In Lisp, we may assume all data items are stored in the heap––but an implementation of Lisp might actually store some small immutable data items (e.g., small integers) in the locations of variables whose values are those data items, and those variables’ locations need not be in the heap.

Data stored in the heap is accessed via variables that store references/ pointers to that data. Note that those variables’ locations may well have been statically allocated or stack-allocated. However, some variables’ locations are heap-dynamically allocated: The locations of indexed variables that are elements of heap-dynamically allocated arrays and instance variables of heap-dynamically allocated objects are heap-dynamically allocated as a part of those arrays / objects.

When are heap-dynamically allocated memory locations allocated?

During program execution, when creating data items that will be stored in the heap.

When are heap-dynamically allocated memory locations deallocated?

Implementations of Java, Lisp, and many modern languages are equipped with an automatic memory management system called a garbage collector that will at certain times try to find and deallocate heap-dynamically allocated locations that the program is no longer able to access. But in most of these languages (including Java and Lisp) a programmer cannot be sure that a particular inaccessible location will actually be deallocated, and has no way to demand that particular heap-dynamically allocated locations be deallocated.

In contrast, C++ allows programmers to explicitly deallocate heap-dynamically allocated locations that will not be used again; delete does this. A program is said to have suffered a memory leak when there are heap-dynamically allocated locations the program is no longer able to access that will not be deallocated before the program terminates. When a memory location is deallocated, any pointers that still point to the deallocated location become dangling pointers whose use would be an error (as deallocated locations may be reallocated for other purposes). C++ programmers often use smart pointers (std::unique_ptr, std::shared_ptr, and std::weak_ptr) instead of ordinary (“raw”) pointers to avoid memory leaks and also avoid creation of dangling pointers.

The TinyJ Virtual Machine’s Memory

The TinyJ VM’s memory consists of the EXPRSTACK, data memory, code memory, and some registers.

EXPRSTACK

The EXPRSTACK (or expression evaluation stack) is used when an expression is being evaluated: Values of the expression’s operand subexpressions are placed in the EXPRSTACK, and the expression’s value will be in the topmost EXPRSTACK location immediately after the value has been found.

Data Memory

Data memory is subdivided into three areas:

- The statically allocated area of data memory is used to store values of static TinyJ variables and characters of TinyJ string literals.

- The stack-allocated area of data memory is used to store values of parameters and other local variables of TinyJ methods. This and the EXPRSTACK are the two stacks of the TinyJ VM.

- The heap area of data memory is used to store TinyJ arrays.

Code Memory

Code memory is used to store TinyJ VM instructions for execution. Its contents will not change during execution of a TinyJ program. Code memory and data memory have separate address spaces.

Registers

Information regarding the roles of registers will be provided in the TinyJ Assignment 3 document.

Static and Stack Memory Allocation Rules Used by the TinyJ Compiler

Static Memory Allocation for Static TinyJ Variables

The nth static int or array reference variable in a TinyJ source file is given the data memory location whose address is n –1. (So the address of the first such variable is 0.) This rule does not apply to Scanner variables: In TinyJ, Scanner variables are fictitious variables; no space is allocated to them.

Static Memory Allocation for TinyJ String Literals

The kth string literal character in the source file is placed into the data memory location whose address is m+k, where m is the last address allocated to a static variable. (In this respect TinyJ differs from Java: In Java, string literals are String objects and are stored in the Java VM’s heap like all other Objects.)

Stack Memory Allocation for Parameters and Other Local Variables of TinyJ Methods: Stackframes of Method Calls and How Locations Within Stackframes are Allocated

Each time a method is called during program execution, a block of contiguous data memory locations known as the call’s stackframe or activation record is allocated; this block of memory locations will be deallocated when the method returns to its caller. Each formal parameter* of the method and each local variable declared in the method’s body will be allocated a location within that stackframe––see the allocation rules below. Each location within the stackframe is referred to by its offset relative to the stackframe location at offset 0. (If in a certain stackframe the data memory address of the location at offset 0 is 73, then the data memory address of the stackframe location at offset +5 is 73 + 5 = 78.)

Memory Allocation Rule for Local Variables Declared in TinyJ Method Bodies

Whenever the compiler sees a declaration of a local variable other than a Scanner variable in the body of a method, that local variable is given the first stackframe location with offset ≥ +1 which has NOT already been allocated to another local variable that is still in scope. (So, ignoring Scanner variables, the stackframe offset of the first local variable in each method’s body is +1.)

Example

int func()

{

int a, b[], c;

...

if ( ... ) {

int d, e[];

...

}

else {

int f, g;

...

int h;

...

}

...

int i;

...

}

In this example:

- a gets offset 1

- b gets offset 2

- c gets offset 3

- d gets offset 4

- e gets offset 5

When f is declared, d and e are out of scope. So:

- f gets offset 4

- g gets offset 5

- h gets offset 6

When i is declared, f, g, and h are out of scope. So:

- i gets offset 4

Memory Allocation Rule for Formal Parameters of TinyJ Methods

Formal parameters are given locations with negative offsets; the last formal parameter of the method gets the stackframe location at offset –2, the second-last parameter gets the location at offset –3, etc.

Example

In a stackframe of any call of int g(int p, int q[], int r):

- r gets offset –2

- q gets offset –3

- p gets offset –4

This does not apply to main( )’s parameter: In TinyJ––unlike Java––main( )’s parameter is not a real parameter. (main( )’s stackframe has no locations with negative offsets.)

Use of Offsets 0 and –1

[This subsection is relevant mainly to TinyJ Assignment 3.]

Dynamic/Control Link

In each stackframe other than main( )’s stackframe, the dynamic/control link is stored at offset 0. (In main( )’s stackframe, the location at offset 0 stores an implementation-dependent pointer.) In stackframes of methods other than main( ), the dynamic/control link is a pointer to the data memory location at offset 0 in the stackframe of the method’s caller.

Return Address

In each stackframe other than main( )’s stackframe, the return address is stored at offset –1. The return address is the code memory address of the next VM instruction to be executed after the current method returns control to its caller. (In main( )’s stackframe there’s no location at offset –1.)

Allocation and Deallocation of Stackframes: An Example

Suppose a TinyJ program has methods main, f(), g(), h(), and this happens when it is executed:

(1) main() is called

(2) main() calls f()

(3) f() calls g()

(4) g() calls h()

(5) h() calls f()

(6) f() returns control to h()

(7) h() returns control to g()

(8) g() calls f()

Then stackframes are allocated in data memory at times (1), (2), (3), (4), (5), and (8); stackframes are deallocated at times (6) and (7). Thus there will be just 4 stackframes in data memory immediately after (8). Listed in order of increasing memory addresses, these 4 stackframes will be:

the stackframe of main() allocated for call (1)

the stackframe of f() allocated for call (2)

the stackframe of g() allocated for call (3)

the stackframe of f() allocated for call (8)

Note that the stackframes of h() and f() allocated at times (4) and (5) would no longer exist: The stackframe of f()allocated at time (5) would have been deallocated at time (6), and the stackframe of h()allocated at time (4) would have been deallocated at time (7).

Comment on Scanner Variables

The data memory allocation rules for TinyJ variables do not apply to Scanner variables (such as the local variable userInput of howManyRings() in CS316ex2.java and the static variable input in CS316ex5.java). No memory at all is allocated for Scanner variables in TinyJ. A Scanner variable x in TinyJ can only be used in x.nextInt(). This is executed by reading an integer from the standard input stream System.in (which is usually associated with the keyboard) and returning its value. So the Scanner variable x is completely irrelevant. That is why TinyJ essentially ignores Scanner variables and never allocates memory for them. (In contrast, the Scanner variable x is not irrelevant when a Java program executes x.nextInt(): In Java, a Scanner object need not be associated with System.in––a Scanner object may, for example, be associated with any input file.) In TinyJ, the Scanner variable x in x.nextInt() is there only because we want TinyJ to be a subset of Java so that TinyJ programs will be compilable by a Java compiler.

Effects of Executing Each TinyJ Virtual Machine Instruction

“Push” and “pop” refer to the TinyJ VM’s expression evaluation stack (the EXPRSTACK).

Notation

- n denotes an arbitrary nonnegative integer

- addr denotes an arbitrary code memory address

- a denotes an arbitrary data memory address

- a’ denotes an arbitrary data memory address ≥ a

- s denotes an arbitrary stackframe offset in the currently executing method activation’s stackframe

If an assumption made by a VM instruction is not satisfied when the instruction is executed (e.g., if the item popped by LOADFROMADDR is not a pointer), the effects of executing the instruction are unspecified.

TinyJ VM Instructions Reference

| TinyJ VM Instruction | Effects of Executing the Instruction |

|---|---|

| STOP | Halts the machine. |

| NOP | Does nothing. |

| DISCARDVALUE | Pops an item. |

| PUSHNUM n | Pushes the nonnegative integer value n. |

| PUSHSTATADDR a | Pushes a pointer to the data memory location whose address is a. |

| PUSHLOCADDR s | Pushes a pointer to the data memory location that is at offset s in the currently executing method activation’s stackframe. |

| SAVETOADDR | Pops an item v. Pops an item p, which is assumed to be a pointer to a data memory location. Stores v in the memory location to which p points. |

| LOADFROMADDR | Pops an item p, which is assumed to be a pointer to a data memory location. Pushes the value that is stored in the memory location to which p points. |

| WRITELNOP | Writes a newline to the screen. |

| WRITEINT | Pops an item i, which is assumed to be an integer. Writes the integer i to the screen. |

| WRITESTRING a a’ | Assumes that the data memory locations whose addresses are ≥ a but ≤ a’ contain the characters of a string literal. Writes that literal to the screen. |

| READINT | Assumes the character sequence of an int will be entered on the keyboard. Reads that character sequence and computes the int value it represents. Pushes that integer value. |

| CHANGESIGN | Pops an item i, which is assumed to be an integer. Pushes the value –i. |

| NOT | Pops an item b, which is assumed to be the value 1 or the value 0.* Pushes the value 1 if b is 0; pushes the value 0 if b is 1.* |

| ADD, SUB, MUL, DIV, MOD, AND, OR which correspond to the Java binary operators +, –, *, /, %, &, | |

Pops an item i and then pops an item j; these are assumed to be integers.* Pushes the value j op i, where op is the operator corresponding to the instruction.* |

| EQ, NE, LT, GT, LE, GE which correspond to the Java binary operators ==, !=, <, >, <=, >= |

Pops an item i and then pops an item j; these are assumed to be integers. Pushes the value 1 or 0 according to whether j op i is true or false, where op is the operator corresponding to the instruction.* |

| JUMP addr | Loads addr into the program counter register. |

| JUMPONFALSE addr | Pops an item b, which is assumed to be the value 1 or the value 0.* Loads addr into the program counter register if (and only if) b is 0. |

| PASSPARAM | Allocates 1 location in the stack-allocated part of data memory. Pops an item and stores that item in the allocated location; it is expected that the item which is popped and stored will be the value of an actual argument of a method that is about to be called. |

| CALLSTATMETHOD addr | Allocates 1 location in the stack-allocated part of data memory; this location will be at offset –1 in the callee’s stackframe. Stores the program counter in the allocated location; the stored address is the call’s return address. Loads addr into the program counter register. |

| INITSTKFRM n | Allocates 1 location in the stack-allocated part of data memory; this will be at offset 0 in the current method activation’s stackframe. Stores the frame pointer in the allocated location; this will serve as the stackframe’s dynamic/control link pointer. Loads a pointer to the allocated location into the frame pointer register. Allocates n more locations in the stack-allocated part of data memory; these will be the locations at offsets 1 through n in the current method activation’s stackframe. |

| RETURN n | Assumes n is the number of parameters of the currently executing method. Assumes the location at offset 0 in the currently executing method activation’s stackframe contains the dynamic/control link pointer. Assumes the location at offset –1 in the currently executing method activation’s stackframe contains the return address. Loads the dynamic/control link pointer into the frame pointer register. Loads the return address into the program counter register. Deallocates the data memory locations that constitute the currently executing method activation’s stackframe. |

| HEAPALLOC | Pops an item i, which is assumed to be a nonnegative integer. Allocates i+1 contiguous locations* in the heap area of data memory; it is expected that the second through i+1st of those locations will be used to store the elements of an array of i elements. Stores in the first of the i+1 locations a pointer† to the first location above the i+1 locations; the second through i+1st locations will all contain 0. Pushes a pointer to the second of the i+1 locations. |

| ADDTOPTR | Pops an item i, which is assumed to be a nonnegative integer. Pops an item p, which is assumed to be a pointer to the data memory location of the first element of an array arr. Pushes p+i (which is a pointer to the location of the array element arr[i]), unless arr has ≤ i elements in which case an error is reported. |

IMPORTANT: The TinyJ compiler generates code that represents the Boolean values true and false by the integer 1 and the integer 0, respectively.

If there isn’t enough available memory in the heap area of data memory to do this, garbage collection will be performed (to deallocate any currently allocated heap locations that can no longer be accessed by the program) and then another attempt will be made to allocate i+1 contiguous heap locations.

† ADDTOPTR uses this pointer to check for array-index-out-of-range errors. The garbage collector uses this pointer to find the ends of allocated blocks.

Example: TinyJ Compiler Code Generation for Assignment 2

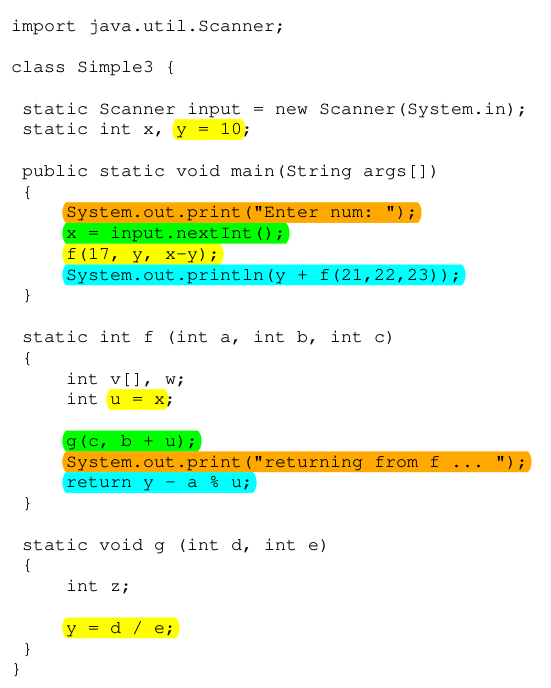

The TinyJ Compiler of Assignment 2 should translate the following TinyJ source file into the TinyJ VM instructions shown below.

Input Source File

Generated Instructions

Code Generation Rules Used by the TinyJ Compiler

-

The generated code begins with instructions which initialize each static int and static array reference variable that has an explicit initializer. [Example: The instructions at addresses 0 – 2 in the code generated for the Simple3 source file.]

-

For variables that do not have an explicit initializer, no initialization code is generated. Static variables that are not explicitly initialized will have a value of 0 (in the case of static int variables) or null (in the case of static array reference variables) when code execution begins: In the TinyJ VM, the data memory locations allocated to static variables all contain 0 when execution begins, and the null pointer is represented by 0.

-

Method bodies are translated in the order in which they appear. [Example: The code generated for main()’s body appears before the code generated for other methods’ bodies.]

-

The code generated for each method (including main) starts with:

INITSTKFRM <total number of stackframe locations needed for local variables declared in that method's body>[Example: The instructions at addresses 3, 34, and 60.]

-

main()’s code ends with:

STOP[Example: The instruction at address 33.] -

The code generated for each void method (other than main()) ends with:

RETURN kwhere k is the number of formal parameters that the method has. [Example: The instruction at address 68.] -

A return expression; statement in a method is translated into:

<code which leaves the value of expression on top of EXPRSTACK> RETURN kwhere k is the number of formal parameters that the method has. [Example: The instructions generated for

return y-a%u;at addresses 51 – 59.] -

A method call

f(arg1, arg2, ..., argk)that is not a standalone statement (and which must therefore return a value) is translated into:‹code that leaves the value of arg1 on top of EXPRSTACK› PASSPARAM ‹code that leaves the value of arg2 on top of EXPRSTACK› PASSPARAM ... ‹code that leaves the value of argk on top of EXPRSTACK› PASSPARAM CALLSTATMETHOD ‹address of the first instruction in method f()'s code›

[Example: The instructions generated for

f(21, 22, 23)at addresses 23 – 29.] -

A method call that is a standalone statement is translated in the same way as a method call that is not, except that the CALLSTATMETHOD may be followed by DISCARDVALUE, NOP, or neither:

- (a) If the called method is known to return a value (either because it has already been declared to return a value, or because the compiler has already seen a call of the method that must returns a value) then the CALLSTATMETHOD will be followed by DISCARDVALUE to pop the returned value off EXPRSTACK.

- (b) If the called method has already been declared as a void method, then no DISCARDVALUE instruction is generated.

- (c) If the called method has not yet been declared, and the compiler has not already seen a call of the method that must return a value, then the compiler does not know if the method returns a value or not. In this case, the compiler essentially leaves a one-instruction gap after generating the CALLSTATMETHOD instruction. Later, when the compiler sees the declaration of the called method, it fills in the gap with either a NOP or a DISCARDVALUE instruction, according to whether the called method is declared to be a void method or a method that returns a value. [Examples: The instructions generated for

f(17, y, x-y)at addresses 8 – 20, and the instructions generated forg(c, b+u)at addresses 39 – 49.]

How Your Assignment 2 Compiler Should Translate TinyJ Source into TinyJ VM Code

Your compiler should perform recursive descent translation.

Notation

For any non-terminal node n in the parse tree of a TinyJ source file, let n.code denote the sequence of TinyJ VM instructions that should be generated by your compiler for the corresponding sequence of tokens (i.e., the VM instructions that should be generated for the sequence of tokens that are the leaves of the subtree whose root is the node n).

Examples

Example 1: If n is the <statement> node in the parse tree of the above program that corresponds to the statement y = d / e; in the body of the method g, then n.code = the instructions at code memory addresses 61 – 67

Example 2: If n is the <expr2> node in the parse tree of the above program that corresponds to the expression d / e in the statement y = d / e;, then n.code = the instructions at code memory addresses 62 – 66

Recursive Descent Translation

Assuming the input file is a valid TinyJ program, when the parser of TinyJ Assignment 1 is executed there is one call of method N( ) for each occurrence n of a nonterminal <_N_> in the program's parse tree.

In Assignment 1, that call of N( ) reads in the corresponding sequence of tokens* from the input file and outputs the subtree of the parse tree whose root is n (and whose leaves are those tokens).

*with the exception of the first of those tokens, as CurrentToken should correspond to that token when N( ) is called.

This is still true when the recursive descent translator of TinyJ Assignment 2 is executed, but in Assignment 2 the same call of N( ) also generates n.code.

Expression Evaluation

If n is an <exprI> node (where i = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, or 7), then:

n.code is code that leaves the value of the corresponding expression on top of EXPRSTACK. (The TinyJ VM doesn’t use data registers for evaluating expressions but uses the EXPRSTACK.)

Detailed Example: Expression Translation

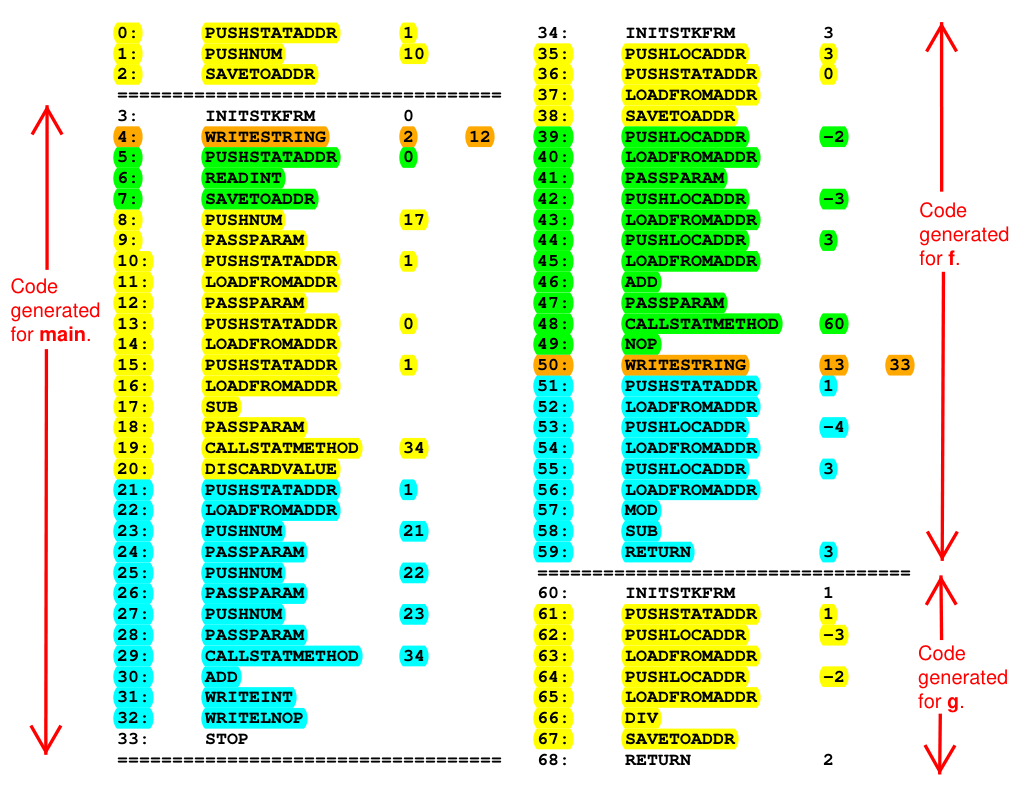

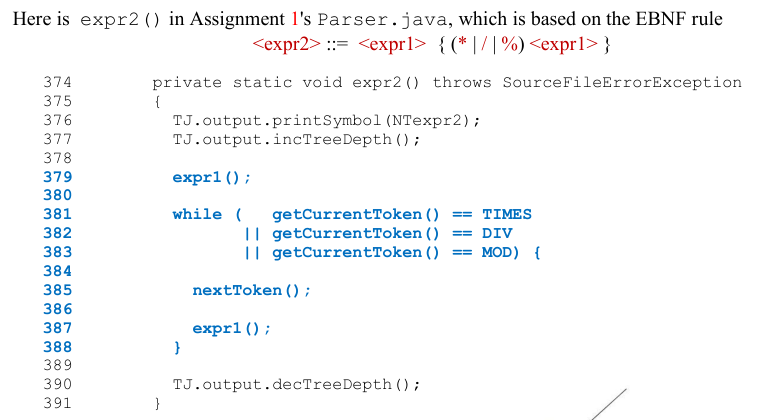

Suppose n is an <expr2> node that corresponds to: 7 * t / (t+3) % h(17,9)

Recalling from Assignment 1 that the EBNF rule for <expr2> is

<expr2> ::= <expr1> { (* | / | %) <expr1>}

we see the subtree rooted at this <expr2> node has the following structure:

In this case:

‹expr2›.code = ‹expr1›0.code

‹expr1›1.code

MUL

‹expr1›2.code

DIV

‹expr1›3.code

MOD

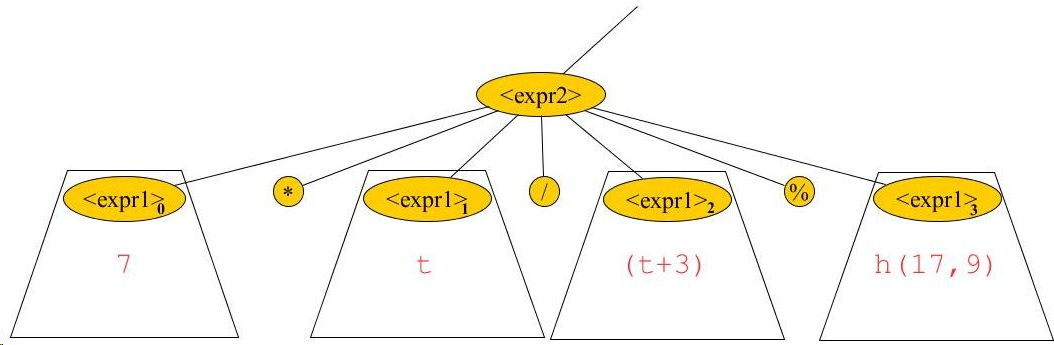

To make this same example more concrete, assume that in 7 * t / (t+3) % h(17,9):

tis astaticvariable whose address is5.his a method whose VM code begins at address 91 in code memory.

Then:

<expr2>.code = <expr1>0.code —— PUSHNUM 7

<expr1>1.code —— PUSHSTATADDR 5

LOADFROMADDR

MUL —— MUL

<expr1>2.code —— PUSHSTATADDR 5

LOADFROMADDR

PUSHNUM 3

ADD

DIV —— DIV

<expr1>3.code —— PUSHNUM 17

PASSPARAM

PUSHNUM 9

PASSPARAM

CALLSTATMETHOD 91

MOD —— MOD

Original Image

How the Compiler Can Generate a VM Instruction

There is a class in the TJasn.virtualMachine package for each kind of instruction.

To generate an instruction, create a new instance of that class; if the instruction has one or two operands, pass these operands as arguments when invoking the constructor.

Examples

new WRITEINTinstr(); // generates WRITEINT

new JUMPONFALSEinstr(31); // generates JUMPONFALSE 31

new WRITESTRINGinstr(21, 27); // generates WRITESTRING 21 27

The generated instruction is put in the next available location in code memory (which is represented by the ArrayList TJ.generatedCode).

Each time an instruction is generated, a line that reports this is written to the output file. For example:

*** Generating: 35: PUSHLOCADDR -3

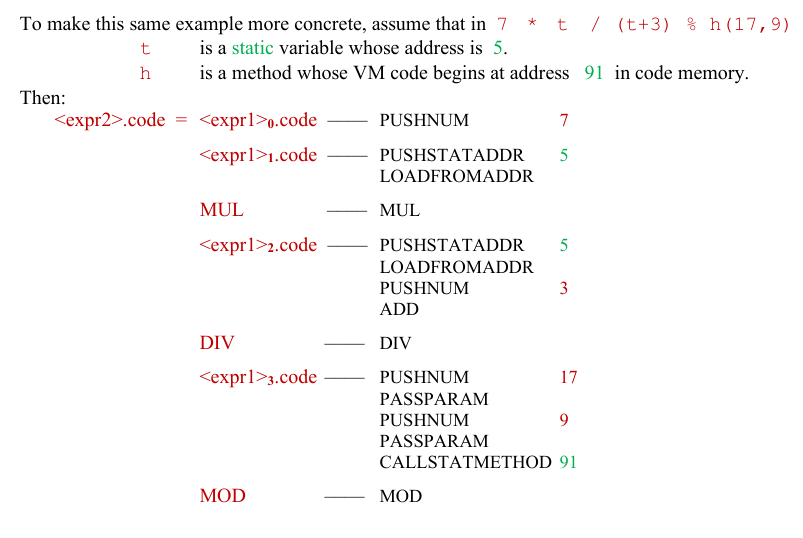

How the Method expr2() in Assignment 1’s Parser.java was Modified for Assignment 2’s ParserAndTranslator.java

Assignment 1’s expr2() Method

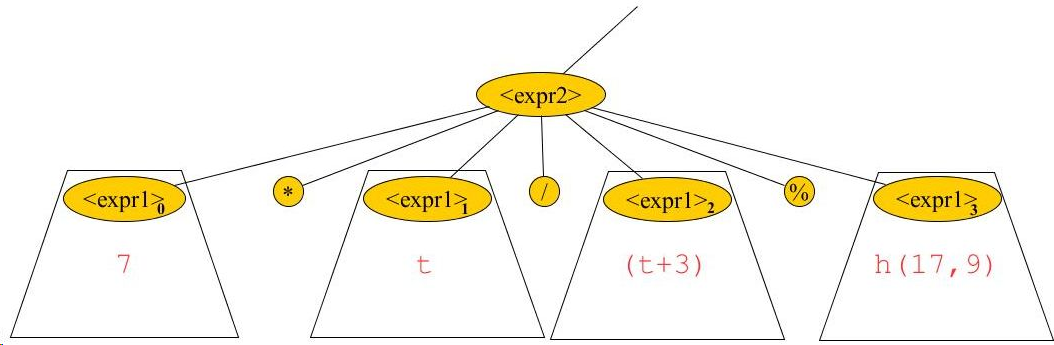

Here is expr2() in Assignment 1’s Parser.java, which is based on the EBNF rule:

<expr2> ::= <expr1> { (* | / | %) <expr1> }

374 private static void expr2() throws SourceFileErrorException

375 {

376 TJ.output.printSymbol(NTexpr2);

377 TJ.output.incTreeDepth();

378

379 expr1();

380

381 while ( getCurrentToken() == TIMES

382 || getCurrentToken() == DIV

383 || getCurrentToken() == MOD) {

384

385 nextToken();

386

387 expr1();

388 }

389

390 TJ.output.decTreeDepth();

391 }

Original Image

Generating Code for expr2()

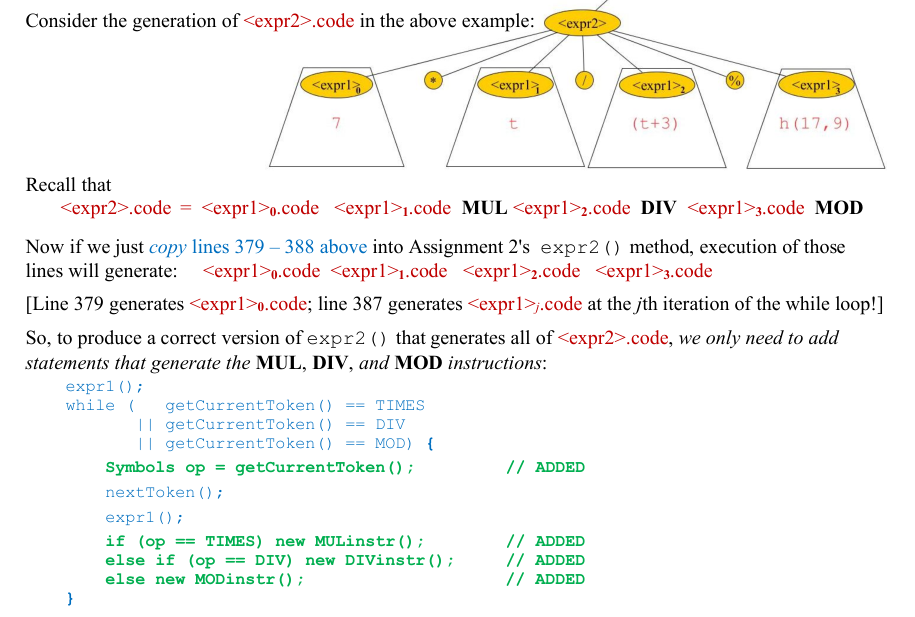

Consider the generation of <expr2>.code in the above example:

Recall that:

<expr2>.code = <expr1>0.code <expr1>1.code MUL <expr1>2.code DIV <expr1>3.code MOD

Now if we just copy lines 379 – 388 above into Assignment 2’s expr2() method, execution of those lines will generate:

<expr1>0.code <expr1>1.code <expr1>2.code <expr1>3.code

[Line 379 generates <expr1>0.code; line 387 generates <expr1>j.code at the jth iteration of the while loop!]

So, to produce a correct version of expr2() that generates all of <expr2>.code, we only need to add statements that generate the MUL, DIV, and MOD instructions:

expr1();

while ( getCurrentToken() == TIMES

|| getCurrentToken() == DIV

|| getCurrentToken() == MOD) {

Symbols op = getCurrentToken(); // ADDED

nextToken();

expr1();

if (op == TIMES) new MULinstr(); // ADDED

else if (op == DIV) new DIVinstr(); // ADDED

else new MODinstr(); // ADDED

}

Original Image

After reading this page, you should be able to fill in the /* ???????? */ gaps on lines 638 through 682!

Hints Relating to the Gaps on Lines 549 and 610 – 4 in ParserAndTranslator.java

As the method expr2() illustrates, a good way to write a method N() in Assignment 2’s ParserAndTranslator.java that corresponds to a nonterminal

Example 1: argumentList() Method

Consider the method argumentList() in ParserAndTranslator.java. We see from p. 1 of the Assignment 1 document that the EBNF rule for <argumentList> is:

<argumentList> ::= '(' [<expr3> { , <expr3> }] ')'

Note that there may be any number of <expr3>’s (and possibly none at all) between the opening and closing parentheses. Based on this, and the part of Code Generation Rule 8 that relates to the list of arguments, we see that:

<argumentList>.code = <expr3>₁.code

PASSPARAM

<expr3>₂.code

PASSPARAM

...

<expr3>ₖ.code

PASSPARAM

where k is the number of <expr3>’s in the <argumentList>, and <expr3>ᵢ means the ith of those k <expr3>’s.

Assuming you correctly filled in the gap in the method argumentList() in Assignment 1, if you copy just that code into the body of Assignment 2’s argumentList() then its calls of expr3() will generate <expr3>₁.code, <expr3>₂.code, …, <expr3>ₖ.code. To complete Assignment 2’s argumentList() method, you would also need to insert one or more statements of the form new PASSPARAMinstr(); in appropriate places to generate the k PASSPARAM instructions.

Example 2: outputStmt() Method

Consider the method outputStmt() in ParserAndTranslator.java. We see from the EBNF rule for <outputStmt> that there are three cases:

<outputStmt> ::= System . out . print '(' <printArgument> ')' ;

| System . out . println '(' [ <printArgument> ] ')' ;

In case 1, the code to be generated is:

<outputStmt>.code = <printArgument>.code WRITEINT

In case 2, the code to be generated is:

<outputStmt>.code = WRITELNOP

In case 3, the code to be generated is:

<outputStmt>.code = <printArgument>.code WRITEINT WRITELNOP

Assuming you correctly filled in the gap in the method outputStmt() in Assignment 1, if you copy just that code into the body of Assignment 2’s outputStmt() then its calls of printArgument() will generate <printArgument>.code in cases 1 and 3. To complete Assignment 2’s outputStmt(), you would also need to insert one or more statements of the form new WRITELNOPinstr(); to generate the WRITELNOP instructions in cases 2 and 3.

Hints Relating to the Gaps on Lines 627, 723, and 593 in ParserAndTranslator.java

The Method printArgument() [gap on line 627]

The relevant EBNF rule is <printArgument> ::= CHARSTRING | <expr3>

(a) In the case <printArgument> ::= <expr3> the code to be generated is:

<printArgument>.code = <expr3>.code

WRITEINT

Assuming you correctly filled in the gap in the method printArgument() in Assignment 1, if you copy just that code into the body of Assignment 2’s printArgument() then its call of expr3() will generate <expr3>.code. To complete the printArgument() method, you would also need to insert a new WRITEINTinstr(); statement.

(b) In the case <printArgument> ::= CHARSTRING the code to be generated is:

<printArgument>.code = WRITESTRING a b

where a and b are the data memory addresses of the first and last characters of the CHARSTRING string literal that is to be printed. The WRITESTRING a b instruction can be generated by new WRITESTRINGinstr(a,b); with the appropriate addresses a and b; but how can your code find the two addresses a and b?

The solution is provided by the lexical analyzer: When LexicalAnalyzer.nextToken() sets LexicalAnalyzer.currentToken to CHARSTRING, it also sets the private variables LexicalAnalyzer.startOfString and LexicalAnalyzer.endOfString to the addresses of the memory locations where the first and last characters of the CHARSTRING will be placed. LexicalAnalyzer.getStartOfString() and LexicalAnalyzer.getEndOfString() are public accessor methods that return the two addresses.

The Method expr1() [gap on line 723]

The relevant EBNF rule is

<expr1> ::= '(' <expr7> ')'

| ( + | - | ! ) <expr1>

| UNSIGNEDINT

| null

| new int '[' <expr3> ']' { '[' ']' }

| IDENTIFIER ( . nextInt '(' ')' | [ <argumentList> ] { '[' <expr3> ']' } )

The null and the IDENTIFIER ( . nextInt '(' ')' | [<argumentList>] {'[' <expr3> ']'} ) cases have been done for you in ParserAndTranslator.java. Here are hints for the other cases:

(a) In the case <expr1> ::= '(' <expr7> ')' the code to be generated is given by

<expr1>.code = <expr7>.code

Similarly, in the case <expr1> ::= + <expr1>₁ the code to be generated is given by

<expr1>.code = <expr1>₁.code

In these two cases, assuming you correctly completed the body of the method expr1() when doing Assignment 1, if you use that code as the body of Assignment 2’s expr1() then in the first case the call of expr7() will generate <expr7>.code, and in the second case the recursive call of expr1() will generate <expr1>₁.code.

(b) In the case <expr1> ::= - <expr1>₁ the code to be generated is given by

<expr1>.code = <expr1>₁.code

CHANGESIGN

Similarly, in the case <expr1> ::= ! <expr1>₁ the code to be generated is given by

<expr1>.code = <expr1>₁.code

NOT

These two cases are similar to the second case of (a), except that you need to insert a new CHANGESIGNinstr(); or a new NOTinstr(); statement.

(c) In the case <expr1> ::= UNSIGNEDINT the code to be generated is given by

<expr1>.code = PUSHNUM v

where v is the numerical value of the UNSIGNEDINT integer literal. The PUSHNUM v instruction can be generated by new PUSHNUMinstr(v); with the appropriate value v; but how can your code find the value v?

The solution is provided by the lexical analyzer: When LexicalAnalyzer.nextToken() sets LexicalAnalyzer.currentToken to UNSIGNEDINT, it also sets the private variable LexicalAnalyzer.currentValue to the numerical value of the UNSIGNEDINT integer literal. LexicalAnalyzer.getCurrentValue() is a public accessor method that returns this value.

(d) In the case <expr1> ::= new int '[' <expr3> ']' '{' '[' ']' '}' the code to be generated is given by

<expr1>.code = <expr3>.code

HEAPALLOC

Assuming you correctly completed the body of expr1() when doing Assignment 1, if you use that code as the body of Assignment 2’s expr1() then <expr3>.code will be generated by a call of expr3(). You would need to insert a new HEAPALLOCinstr(); statement.

The Method whileStmt() [gap on line 593]

The relevant EBNF rule is:

<whileStmt> ::= while '(' <expr7> ')' <statement>

and the code to be generated is:

<whileStmt>.code = a: <expr7>.code

JUMPONFALSE b

<statement>.code

JUMP a

b:

In Instruction.java, the static variable Instruction.nextCodeAddress is used to hold the code memory address of the next instruction to be generated. [This variable is incremented by 1 (by the constructor for the Instruction class) each time an instruction is generated.]

A call of Instruction.getNextCodeAddress() returns Instruction.nextCodeAddress.

Before calling expr7() to read the <expr7> expression and generate <expr7>.code, whileStmt() needs to call Instruction.getNextCodeAddress() and save the code memory address that is returned in an int local variable (which needs to be declared). This saved address will be needed as the operand a of the JUMP a instruction which whileStmt() must generate later!

Instruction.OPERAND_NOT_YET_KNOWN (line 13 in Instruction.java) is a constant integer that the compiler uses to represent an unknown operand value.

When whileStmt() begins to generate JUMPONFALSE b it does not know what the address b will be. So at that time whileStmt() should merely generate:

JUMPONFALSE Instruction.OPERAND_NOT_YET_KNOWN

and also save a reference to this JUMPONFALSE instruction in a local variable, to allow the instruction to be found again when whileStmt() is ready to fix up its operand:

JUMPONFALSEinstr jInstr = new JUMPONFALSEinstr(Instruction.OPERAND_NOT_YET_KNOWN);

fixUpOperand() is an important method of OneOperandInstruction.java: If instr is a reference to a one-operand VM instruction then instr.fixUpOperand(k) sets that instruction’s operand to the integer k.

So, after generating the JUMP a instruction, whileStmt() can fix up the operand of the previously generated JUMPONFALSE Instruction.OPERAND_NOT_YET_KNOWN instruction as follows:

jInstr.fixUpOperand(Instruction.getNextCodeAddress());

Study the ifStmt() Method [lines 555 – 85]

The above hints should provide enough information for you to complete the method whileStmt(). But you should also study the method ifStmt(), which has already been written for you and provides further examples of how Instruction.OPERAND_NOT_YET_KNOWN, Instruction.getNextCodeAddress(), and fixUpOperand() are used.

Here the relevant EBNF rule is:

<ifStmt> ::= if '(' <expr7> ')' <statement> [ else <statement> ]

and the code to be generated is as follows:

Case 1: <ifStmt> ::= if '(' <expr7> ')' <statement>₁

<ifStmt>.code = <expr7>.code

JUMPONFALSE a

<statement>₁.code

a:

Case 2: <ifStmt> ::= if '(' <expr7> ')' <statement>₁ else <statement>₂

<ifStmt>.code = <expr7>.code

JUMPONFALSE a

<statement>₁.code

JUMP b

a: <statement>₂.code

b:

It is possible that there will be one or more questions on Exam 2 or the Final Exam which test your understanding of the method ifStmt().

Hints Relating to the Gaps on Lines 492, 495, and 511 in ParserAndTranslator.java

Here the relevant EBNF rule is:

<assignmentOrInvoc> ::= IDENTIFIER ( { '[' <expr3> ']' } = <expr3> ;

| <argumentList> ;

)

This rule has two cases:

Case 1: <assignmentOrInvoc> ::= IDENTIFIER { '[' <expr3> ']' } = <expr3>;

Case 2: <assignmentOrInvoc> ::= IDENTIFIER <argumentList> ;

The gaps you have to fill in relate only to Case 1. In that case the code to be generated is as follows:

<assignmentOrInvoc>.code = PUSHLOCADDR IDENTIFIER.stackframe_offset or PUSHSTATADDR IDENTIFIER.address

LOADFROMADDR

<expr3>index_1.code

ADDTOPTR

...

LOADFROMADDR

<expr3>index_k.code

ADDTOPTR

<expr3>right_side.code

SAVETOADDR

where <expr3>right_side means the expression on the right side of =, and where the number of occurrences of:

LOADFROMADDR

<expr3>index_i.code

ADDTOPTR

is equal to the number of indexes after the IDENTIFIER––i.e., the number of times '[' <expr3> ']' occurs. Often there are no indexes (i.e., the assignment is of the form IDENTIFIER = <expr3>right_side ;). In any case the loop on lines 500–507 generates LOADFROMADDR, <expr3>index_i.code, and ADDTOPTR as many times as is needed. But you must fill in the gap on line 511 in such a way that <expr3>right_side.code and SAVETOADDR are generated.

Symbol Table Lookup

Note that the compiler must generate PUSHLOCADDR IDENTIFIER.stackframe_offset if the IDENTIFIER is a formal parameter or a local variable declared in the method’s body, but it must instead generate PUSHSTATADDR IDENTIFIER.address if the IDENTIFIER is a static variable. To determine which of these two cases applies, and to determine the identifier’s stackframe offset in the former case and its data memory address in the latter case, the compiler looks up the IDENTIFIER in the symbol table. The symbol table is a table, maintained by the compiler. When a method’s body is being compiled, the symbol table contains:

- A LocalVariableRec object for each formal parameter of the method, and for each local variable that is declared in the method’s body and is in scope at the point the compiler has reached.

- A ClassVariableRec object for each static variable whose declaration has been seen by the compiler.

The compiler records information about each variable / parameter in its LocalVariableRec or its ClassVariableRec object. For example, if v is a static variable then v’s data memory address is stored in the offset field of v’s ClassVariableRec object. Similarly, if v is a formal parameter / local variable then v’s stackframe offset is stored in the offset field of v’s LocalVariableRec object.

The symbol table also contains a MethodRec object for each method that has been declared or called in the part of the program that has been seen by the compiler. But you will not have to write any code that deals with MethodRec objects to complete Assignment 2.

Implementation Details

Line 480 of ParserAndTranslator.java sets identName to the name of the IDENTIFIER. On line 485, t = symTab.searchForVariable(identName); looks in the symbol table for the IDENTIFIER’s LocalVariableRec or ClassVariableRec object, and sets t to refer to that object. Therefore the Boolean value of t instanceof LocalVariableRec on line 491 will be true or false according to whether the IDENTIFIER is a local variable / formal parameter or is a static variable. In the former case t.offset will contain IDENTIFIER.stackframe_offset; in the latter case t.offset will contain IDENTIFIER.address. Use t.offset to fill in the gaps on lines 492 and 495 in such a way that PUSHLOCADDR IDENTIFIER.stackframe_offset is generated if the IDENTIFIER is a local variable or formal parameter, but PUSHSTATADDR IDENTIFIER.address is generated if the IDENTIFIER is a static variable.